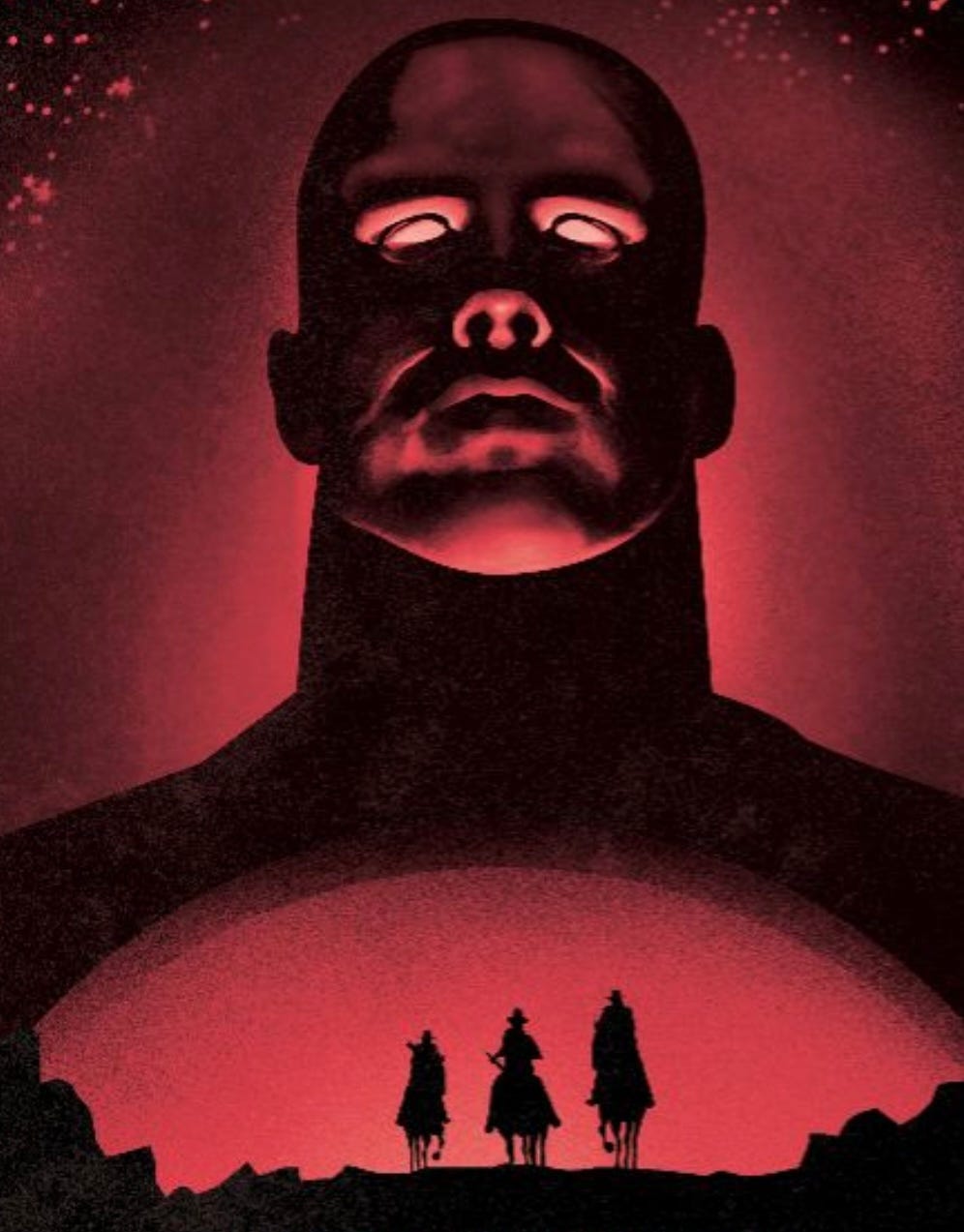

1. What’s He a Judge Of?

In Chapter X of Blood Meridian, Ben Tobin tells the Kid that the first time he met Judge Holden, Glanton’s Gang was out of gunpowder and being pursued by Apaches. Tobin says that the Judge:

“Saved us all. I have to give him that. We come down off the Little Colorado we didn’t have a pound of powder in the company. Pound. We’d not …