1. As If They’d Never Been At All

In the final chapter of Blood Meridian, the Kid has metamorphosed from a teenager into a forty-five-year-old drifter that the narrator calls the Man and McCarthy’s narrative has leapt from the California of the early 1850s to the plains of north Texas in 1878, jumping the apocalypse of 1861-1865.

On the Texas plains, McCarthy’s protagonist meets an old buffalo hunter who tells him of the oceans of bison he first encountered when he came west after the Civil War and of how, in the span of thirteen years, those magnificent creatures have all but vanished:

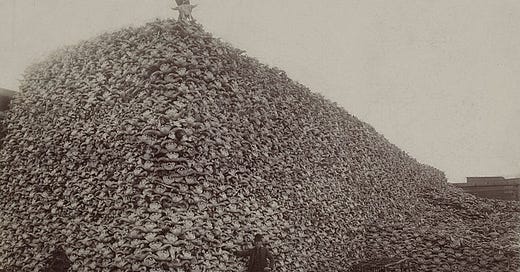

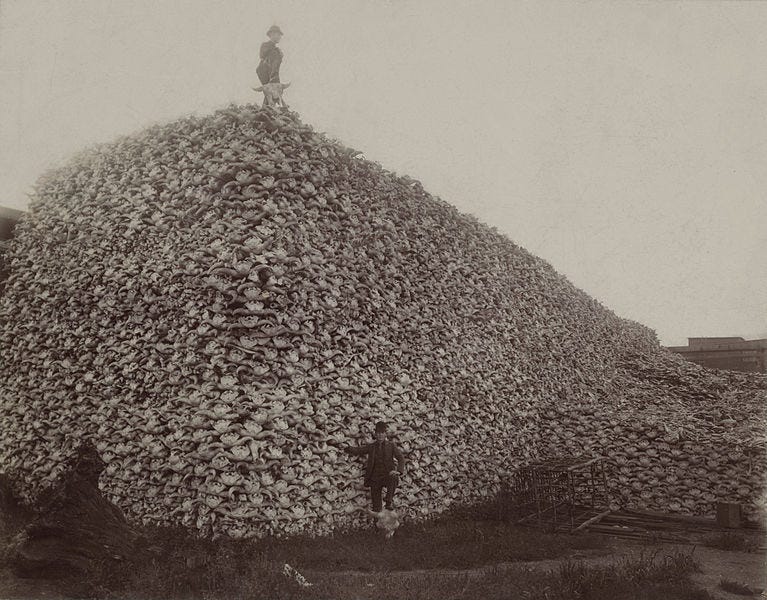

“On this ground alone between the Arkansas River and the Concho there was eight million carcasses for that’s how many hides reached the railroad. Two year ago we pulled out from Griffin for a last hunt. We ransacked the country. Six weeks. Finally found a herd of animals and we killed them and come in. They’re gone. Ever one of them that God ever made is gone as if they’d never been at all” (330).

The hunter seems struck by the disappearance of these animals, but the reader isn’t. We know what happened to the bison.

In the years after the Civil War, men and their families flooded west. 700,000 Americans had died in the unspeakable carnage that shocked a divided nation from 1861-1865. The Southern States were in ruins, especially Virginia, Mississippi, Tennessee, Georgia, and both Carolinas—those last three because of the vengeance campaign of William Tecumseh Sherman.

The North had lost 365,000 military-age men; 300,00 more had been horribly maimed and disabled for life, many more bore psychological scars from the combat they’d seen.

For the able-bodied men who’d survived the horrors of modern warfare, the world looked like a drastically-different place. Seeking a new beginning, tens of thousands of veterans—Northern and Southern alike—began to make their way west.

Many were looking for redemption in a land unspoiled by war, but they ended up reenacting the same hell they’d witnessed at places like Shiloh, Antietam, and Cold Harbor.

These are the men who killed off the buffalo and drove Native People into a nightmarish existence on reservations.

It is interesting that McCarthy’s novel, certainly no stranger to bloodshed and horror, skips the American Apocalypse of 1861-65.

I’d like to take a look at what Blood Meridian passes over, focusing our attention on the McCarthy-esque Battle of Shiloh, then thinking about how traces of this terrible war are present in the book’s final chapter.

2. Unconditional Surrender

Abraham Lincoln took the helm of a fractured nation on March 4th, 1861, but couldn’t manage to find a general whose fighting spirit matched his own.

The first man he selected to lead the Union into battle was a West Point-educated army colonel named Robert Edward Lee. Lee was a Mexican War veteran, an elite soldier with a Revolutionary pedigree: his father was George Washington’s favorite cavalryman and Lee himself went on to marry Washington’s granddaughter. But on April 17th, when his home state of Virginia seceded, Lee turned down Lincoln’s offer, saying he could never draw his sword against his native land. That an officer as prominent as Robert E. Lee considered his native land to be Virginia and not the United States gives some indication of the kind of challenges Lincoln faced as he attempted to form an army capable of coaxing the South back into the Union’s embrace.

For the next year, things only got worse for Lincoln. Despite being outnumbered, the Confederates managed to win nearly every engagement and the North’s general-in-chief, Winfield Scott, was seventy-five and too obese to mount his horse. After Union general George B. McClellan pulled off a pair of minor triumphs at Philippi and Rich Mountain, Lincoln allowed himself to believe he’d found an American Napoleon—which was precisely who McClellan claimed to be. Lincoln gave the young general command of the newly-formed Army of the Potomac, then replaced Winfield Scott with McClellan, making the thirty-five-year-old the nation’s youngest general-in-chief. But McClellan, having trained an impressive army, was unwillingly to use it in combat. The army camped around the nation’s capital: drilling, eating, and costing the Union gargantuan sums of money.

At last, Lincoln became so frustrated with McClellan’s inaction, he sent the man a telegram, telling the general that if he didn’t “want to use the Army, [he] would like to borrow it for a time.”

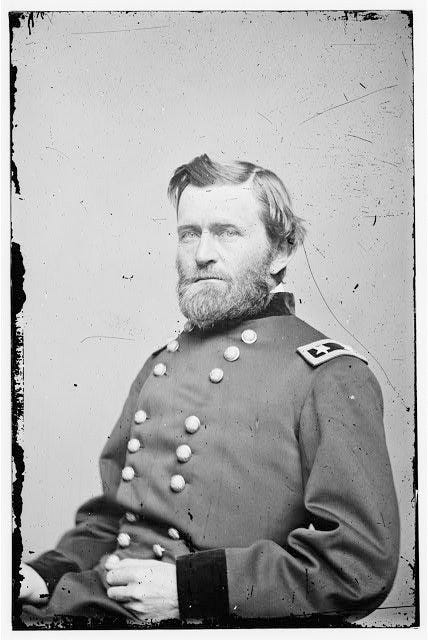

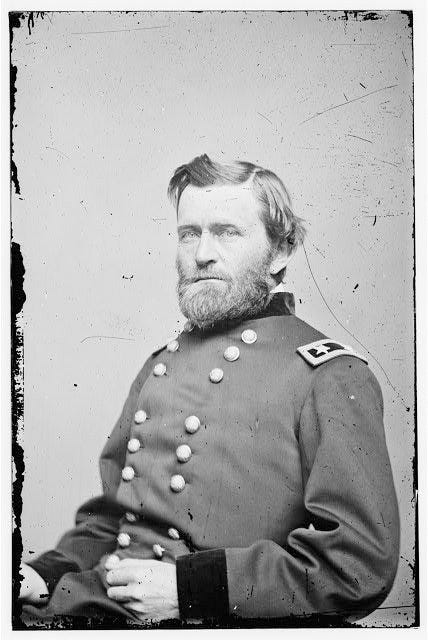

But while the president was struggling with incompetent and procrastinating officers in the eastern theater of the war, Ulysses S. Grant was behaving like a real-life action hero in the west.

After scoring two modest victories at Paducah, Kentucky and Belmont, Missouri, Grant went after a larger prize in the Volunteer State, attacking the Confederate garrison at Fort Henry on the east bank of the Tennessee River. Henry wasn’t really much of a fort: a star-shaped works built on low, swampy ground and sitting below the waterline of the river, this earthen citadel was already starting to flood in the rainy days of February just before Grant’s attack. The night before the Union assault, the Rebel commander at the fort, Brigadier General Floyd Tilghman, held a council of war with his officers and all agreed that Henry must be abandoned. Tilghman would send the lion’s share of his troops twelve miles east to the much better defended Fort Donelson on the west bank of the Cumberland, remaining behind with a skeleton crew to man Fort Henry’s guns.

So, conditions for Union success were quite good on February 6th when Grant took twenty-three regiments up the Tennessee and had naval flag officer Andrew Foote open fire on the Confederate works with his ironclads. Foote’s gunboats were critical in the brief fight to follow—the fort was destroyed before Grant’s infantry could even reach it. When Grant arrived, Tilghman had already surrendered to Foote and the Union flag was snapping in the breeze over the flooding fortress.

Never one to rest on his laurels, Grant had no sooner wired his boss, Henry Halleck, that Fort Henry was theirs, that he further notified Old Brains about his plans to “take and destroy Fort Donelson on the 8th.”

While Fort Henry had been seized with very little effort, Fort Donelson was an altogether different matter. It was believed Donelson “could be held against any onslaught,” as a Memphis newspaperman had written recently. Seizing this fortress on the Cumberland would be a very difficult task, but to Grant that only meant a more significant triumph.

It is worth pausing a moment to examine this plain-spoken brigadier general with a name out of Classical literature. At a time when the North was so starved for victory that most Union commanders would have turned the taking for Fort Henry into the sack of Troy, all this Ohio Ulysses could think about was his next fight. Where did this driving ambition—conspicuously absent from Lincoln’s other generals—come from?

Grant, a short, somber man with his reddish-brown beard and jewel-blue eyes, had experienced so many setbacks in his personal life that he seemed impervious to those he might suffer on the battlefield. A West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran of exceptional courage, he’d been drummed out of the peacetime army in 1854 when he began to drink at the remote outpost of Fort Humboldt in California. He’d had nothing to do but miss his adored wife and children who were back in Missouri, and downtime is a great enemy to any soldier, especially one like Grant. He was overjoyed to return to his family, but civilian life proved more punishing than any battle. He failed first at farming the little spread outside St. Louis that he aptly named Hard Scrabble, then failed at real estate and bill collecting. The winter of 1857 found him selling firewood on the streets of the Gateway City and he pawned his watch to afford Christmas presents. When war broke out in 1861, Grant was working as a clerk in his father’s leather goods store in Galena, Illinois—a job he hated only a little less than destitution.

But the moment he once again donned the uniform of his country his fortunes completely changed. For Grant, they had to: he had nothing to go back to but a family he was sick of disappointing. Having failed at everything in civilian life but marriage and fatherhood, Grant was willing to wager all his chips for victory on the battlefield. Sometimes the returns were massive and sometimes they were modest, but he was all-in, whatever the result, never giving much thought to what the enemy might do to him, consumed rather what he’d do to the enemy.

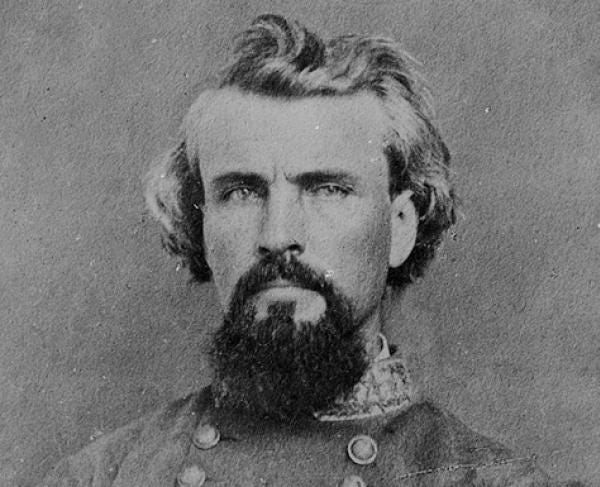

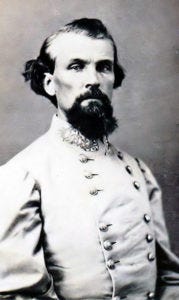

Grant began his campaign against Fort Donelson on February 12th. Waiting for him inside the fortress was a Confederate colonel bound for infamy and three generals headed for obscurity. The infamous Rebel was Nathan Bedford Forrest, who monitored the fall of Fort Henry and the approach of Grant’s army with concern. Forrest and his cavalry would go on to accomplish great and terrible things for the Confederates, but they were useless bottled up inside an installation like Donelson, and even more useless at the service of the three men commanding the fort: Brigadier Generals John B. Floyd, Gideon J. Pillow, and Simon Bolivar Buckner. The latter was the best of these brigadiers and had been Grant’s classmate at West Point. In 1854, when Grant found himself stranded in New York City and was trying to make his way home to his family, he ran into Buckner and the man had loaned him money, a kindness which Grant never forgot.

Unlike its poorly defended sister fort on the Tennessee River, Donelson sat on a hill overlooking the Cumberland and had serious artillery at its disposal. 17,000 Confederate troops manned the trenches on the morning Grant marched his 15,000 soldiers overland from Fort Henry. Bedford Forrest and his cavalry were permitted to ride out and harass Grant’s men, but were soon recalled by Buckner, and the Union troops were able to advance on Donelson, cutting off Rebel escape routes.

A single gunboat, the USS Carondelet, came upriver and began to test the fort’s defenses, shelling the Rebels. But the Carondelet wasn’t a serious threat—the gunboat had to fire up at the fortress, its shells fighting gravity—and was soon forced to withdraw.

Grant set up his headquarters at a nearby farmhouse and the first day of the battle came to a close. He planned to make a proper go of it the next morning, hoping he’d awaken to see Andrew Foote’s ironclads steaming up the Cumberland; they were currently being repaired after the engagement at Fort Henry.

Come daylight, there were skirmishes between the Yankees and Rebels, but nothing was gained either way, and when darkness fell on the night of February 13th the temperature plunged to ten degrees. A storm blew in; rain poured, turning to sleet and then snow—three inches of it by morning. Out in the field, Union men—many of who had abandoned their overcoats and blankets on the warm, sunny march to Donelson—stamped around blowing into their hands to stave off frostbite. They weren’t allowed to make campfires for fear of enemy snipers and suffered a miserable, sleepless night.

But while the Yankees were shivering in their frozen uniforms, the Rebel commander, General Floyd, had begun to quake for a different reason. Comfortable ensconced in his headquarters at the Dover Hotel, Floyd and the officers with him decided that Fort Donelson couldn’t be held after all and plans were drawn up for a escape attempt to keep the Union from capturing their army.

On the afternoon of the 14th, Flag Officer Foote and his gunboats arrived to Grant’s great relief: four ironclads, two wooden gunboats, and twelve transport ships with 10,000 Union reinforcements. Grant now outnumbered the Rebels and had a proper naval force to boot. The sober and determined Foote wasted no time: he immediately started shouting orders at his gunners through the megaphone he carried so as to be heard over the roar of his ship’s steam engine, directing fire on Fort Donelson.

But his artillery, so effective at the Battle of Fort Henry, was less so here. While he’d been firing down into the low-lying Henry, Foote found that the guns of Fort Donelson were sending plunging fire down to him. The Rebel gunners gave his boats a pounding which grew worse the closer he got. His shells either did little damage or overshot their intended target and struck Union forces on the other side of Donelson. There were fifty-four Union casualties and Foote was himself wounded in the ankle. After an hour and a half, Foote withdrew, chugging his little fleet back down the Cumberland as Rebels rose from their trenches, cheering.

With darkness came a replay of the previous night: Union soldiers shivering outside the fort and Confederate commanders quivering within. In effect, the Rebels had been victorious this day, but now they were trapped. All three generals were inside Fort Donelson this evening—Floyd, Pillow, and Buckner—and all three agreed that it was only a matter of time before the fortress was taken; they had to break out.

Early morning of the 15th, Foote summoned Grant to his ship for a conference and Grant was rowed out to speak with the flag officer. Though a salty fighting man, Foote couldn’t do much with gunboats that had been wrecked by Rebel artillery—he wanted to go back downriver to have them fixed and refitted. Grant persuaded him to take only the two worst-affected ships and leave him the rest; Foote acquiesced. Grant came back ashore around noon only to find that, in his absence, everything had fallen apart. While on Foote’s flagship, the Confederates had launched a vicious counterattack. Nathan Bedford Forrest and his cavalry had flanked Grant’s second-in-command, Brigadier General John McClernand, and driven his men back. Union troops were taking punishment all up and down the line, had been pushed back a mile in some places and two in others. In the words of a panicked Union messenger sent to Lew Wallace’s camp, “The whole army is in danger!”

McClernand’s position, crucial to Grant’s assault on Donelson, had been seized by the Rebels, but McClernand refused to take responsibility for his failure to firmly anchor his line, leaving it vulnerable to the flanking maneuver Forrest’s cavalry had executed. The victories Grant had won at Paducah, Belmont, and Henry would mean nothing if he was defeated here. He must have felt like everything he’d accomplished was slipping away. It was.

An essential component of Grant’s character and a key reason for his success is that he neither panicked nor showed outward signs of distress. Remaining cool and confident, he calmly informed McClernand that his position would have to be retaken. Then, walking past a line of Rebel POWs, he noticed that the men’s knapsacks contained three-days rations and correctly read the Confederates’ intentions: they weren’t equipping their soldiers for a prolonged attack; they were provisioning them for an escape.

Grant immediately set about directing his men to recapture the ground they’d lost and by evening, they’d managed to do so, repulsing the Rebels and turning disaster’s tide. Trotting back to his headquarters in the iron-blue dusk, Grant happened on a wounded Union officer and Confederate private lying on the frozen ground. Dismounting, he conjured up a flask of brandy from his staff, gave each man a swig, then called up troopers with Satterlee stretchers to carry the soldiers off the field. When he saw his boys in blue ignoring the injured Rebel, he gave an order that was trademark Grant, demanding the stretcher-bearers “take this Confederate too. Take them both together: the war is over between them.”

Grant’s courage and compassion outside Donelson is a stunning contrast to the cowardice and vaudevillian comedy taking place inside the fort. Certain that the Union army would overrun their position the following day, Brigadiers Floyd and Pillow decided to sneak out of Donelson and leave the honorable Buckner holding the deflated ball. But there was that pesky issue of transfer of power to contend with, so the faint-hearted twosome performed the following routine:

“I turn the command over, sir,” said Floyd to Pillow.

“I pass it,” Pillow informed Bucker.

“I assume it,” Buckner said grimly, eyeing Floyd and Pillow as they prepared to make their escape to Nashville.

Standing nearby, Nathan Bedford Forrest looked on in disgust. He had not come to Donelson just to hand his cavalry over to the Yankees, and seeing that two generals were fleeing while the other was preparing to yield the fort, he called his own officers over and said, “Boys, these people are talking about surrendering, and I am going out of this place before they do or bust hell wide open.”

Then Forrest led his men out of Fort Henry unnoticed, trotting them through a gap in the Union lines along a frozen stream.

Just before dawn the next morning, February 16th, Grant was awakened by one of his officers and informed a Confederate messenger had just ridden in with a letter from his old friend Simon Bolivar Buckner. Perusing the missive, Grant quickly caught its gist: the new Rebel commander was asking what terms Grant would offer if Buckner agreed to surrender Donelson to him.

Grant walked over to the kitchen table and wrote what would become one of the most famous replies in the annals of the Republic:

SIR: —Yours of this date, proposing armistice and appointment of Commissioners to settle terms of capitulation, is just received. No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.

I am, sir, very respectfully,

Your ob’t se’v’t,

U.S. GRANT

Brig. Gen.[v]

Buckner must have swallowed very hard when he read Grant’s answer. Usually, a commander offering to surrender could hope to bargain a little, but this American Ulysses was no businessman: he wouldn’t haggle and he didn’t bluff. Bucker would either surrender as soon as he read Grant’s reply or Grant would reduce Fort Donelson to legend and ash.

Buckner wisely surrendered and word of Grant’s twin victories at Forts Henry and Donelson lit the country on fire. The New York Times wrote that Grant’s “prestige is second now to no general in our army.” He was an instant celebrity, his name praised throughout the North with the same enthusiasm as it was reviled down South. Lincoln was ecstatic when he received news of Grant’s daring triumphs and quickly signed the secretary of war’s nomination promoting Grant to major general.

The Northern papers couldn’t get enough of Grant. They printed a photograph of him where he happened to be holding a cigar and men immediately began sending him boxes of them. Before Henry and Donelson, Grant had been a pipe-smoker. Now he felt obliged to puff his way through the crates of cigars that would never stop arriving, a habit that eventually caused the throat tumor that would kill him at the age sixty-three.

But in the glory days after his victories on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, he was still a young man, just shy of forty. He’d been destitute a few years before and in an few more years he’d be promoted to general-in-chief of all Union armies. In a little over six years, he’d be elected president. Surely, this is the most meteoric rise in all of American History.

The rest of that winter and on into early spring, Grant moved south into Tennessee, driving the Confederates before him. Then, the first week of April, as the Rebels began assembling just below the border at Corinth, Mississippi, Union scouts came upon a place called Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River. It was mere miles from Corinth, steamboats could easily land troops there, and there were level fields where an army could camp and drill.

It sounded good to Grant who was itching to get at the enemy again. He said he “considered the war as good as over” and was just looking for one more big battle where he could bag the Confederate army in the West and put this Rebellion down for good.

3. The Passion of General Sherman

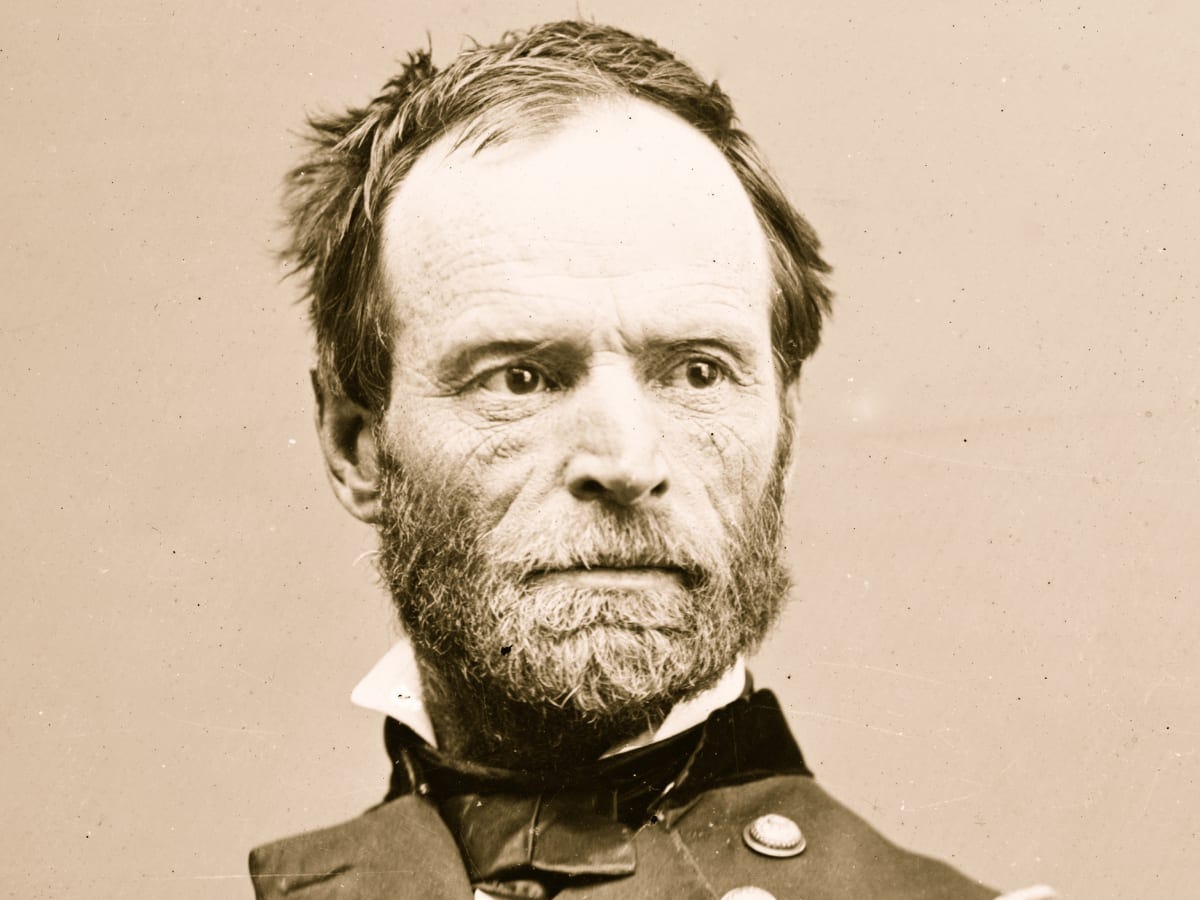

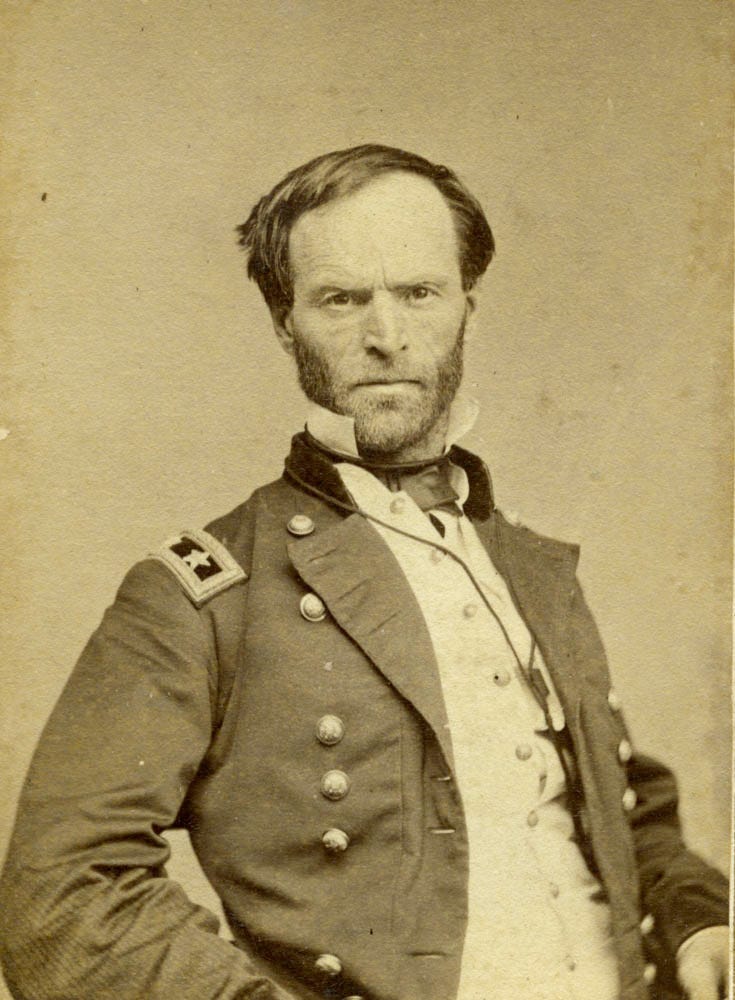

Serving under Grant’s command since the first of March was a forty-two-year-old Ohioan named William T. Sherman.

He stood an inch shy of six feet—red-headed and lean. He was Tecumseh to his father and plain Cump to his friends. There are many photographs of Sherman from the Civil War and he isn’t smiling in a single one; he stares off to the right of the camera, glowering. His beard, though short, had a tendency to grow too far up on his cheeks—something about this and the cowlick on the crown of his head gave him a haggard appearance, even when wearing the uniforms he had specially tailored at Brooks Brothers in New York.

He was brilliant, talkative, brimming with a restless energy that bordered on mania. Just before war broke out in spring of 1861, he’d been serving as superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning & Military Academy—known today as LSU. Sherman resigned the post when Louisiana seceded, but not before blasting the Bayou State and informing Southerners just how doomed their new Confederacy was.

“You people speak so lightly of war,” he told friend and professor David French Boyd, “you don’t know what you are talking about.” In typical Cump fashion, he ranted on:

You mistake the people of the North. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it. The North can make a steam engine, locomotive or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical and determined people on earth—right at your doors. Only in spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. In the end you will surely fail.

Professor Boyd and Sherman’s other friends should have taken note of this prescient warning. One rarely hears anything pleasant after you people.

As a West Pointer and in-law of the well-connected Ewing family—his younger brother was the U.S. Senator John Sherman—Cump had little difficulty procuring a commission as an infantry colonel. In June, after the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run where Sherman outperformed his incompetent superiors, the War Department issued the star of a brigadier general for the shoulder straps of his uniform and it looked as though Cump’s career as a combat commander was off to an auspicious start.

Then, in the fall of that first year of the war, Sherman ran into trouble. The army sent him to the border state of Kentucky to serve under General Robert Anderson and seize command of the riverways. Whoever “controls the Ohio and the Mississippi will ultimately control this continent,” Sherman had told Salmon P. Chase and this was Lincoln’s view as well. When war broke out, the President had written, “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor, I think, Maryland. These all against us, the job on our hands is too large.”

But under the weight of this difficult task, Sherman started to crack. First, he became convinced that the Rebels had him outnumbered and grew gloomy about Union prospects in the Bluegrass State. He complained constantly to higher-ups about his troops’ lack of arms and the quality of those weapons they did have. He came to believe that Confederate spies had infiltrated his ranks and, imagining the number of enemy troops to be legion, asked to be reinforced. When General Anderson resigned as head of the Department of the Cumberland and Sherman was installed in his place, things went from bad to worse.

Though he was asthmatic and promised his wife he wouldn’t use tobacco, Sherman began to smoke cigars. Instead of sleeping, he spent his nights pacing the floor, exhaling plumes of smoke like an anxious dragon. He imagined being overrun by companies of Confederate troops that did not, in fact, exist. His grip on reality was growing more tenuous by the day.

Having received no comfort from his military superiors, he took to writing letters about his invented problems to President Lincoln, telling the Commander-in-Chief that his troops were “entirely inadequate.” As anyone who’s ever complained to a boss about the insufficiency of his staff knows, this was an extraordinarily bad idea.

Writing about this period of Sherman’s war-time service, biographer and historian James Lee McDonough notes: “The Sherman of Kentucky was far from the confident, conquering general who could successfully lead 100,000 men against the enemy.” It’s difficult to see the indomitable Sherman of the infamous March to the Sea in this panicked, sleepless cigar-smoker, penning letters of complaint to anyone who’d read them.

Sometime between the fall of 1861 and the summer of 1862, William Tecumseh Sherman was transformed.

But before this metamorphosis could take place, Sherman still had farther to fall.

In mid-October, then-Secretary of War Simon Cameron paid Cump a visit at the Galt House in Louisville. Cameron had just left St. Louis where he’d been investigating rumors of corruption surrounding former-adventurer and presidential candidate, John C. Fremont—a rich irony given that Cameron was one of the most corrupt men to ever hold a cabinet position (Thaddeus Stevens opined that the only thing Cameron wouldn’t steal was a red-hot stove). Sherman was thrilled at being given the opportunity to complain to one of superiors in person and begged Cameron and Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas to spend the night.

They met in Sherman’s hotel room for lunch. After eating, Cameron—who was feeling unwell—lay on Sherman’s bed and told the troubled general to unburden himself. In those October days, one usually didn’t have to ask Sherman to do this sort of thing twice, but Cameron had a sizable entourage with him and Cump was hesitant to complain in front of such an audience—in Sherman’s words, “I preferred not to discuss business with so many strangers present.”[xi] He asked if he could speak to Cameron in private.

Sherman would later write how Cameron had told him that his many hangers-on were “all friends, all members of my family, and you may speak your mind freely and without restraint.”

Cameron had no idea what he was asking for: an unrestrained Sherman was never something anyone had requested. No one would request it again until Grant decided to take Sherman off the leash and sic him on Georgia in November of ‘64.

But while Cameron failed to grasp just what a dangerous frame of mind Sherman was in, Cump didn’t realize that his most pressing danger didn’t come from Confederates in Mill Springs, 150 miles to the south, but from a member of the Secretary of War’s entourage seated fifteen feet away.

Sherman glanced around the room, considering how it might feel to unburden himself—there were, indeed, some strange faces among those assembled, one belonging to Samuel Wilkerson, a correspondent for the nation’s largest daily newspaper of the time, the New-York Tribune. Wilkerson was unknown to Sherman and sat quietly making notes. If Sherman would’ve had any inkling of the misery this man was about to cause him, Wilkerson’s fate might have been the same as Georgia’s three years later.

But Sherman had no such inkling. He rose, walked over to the door and locked it. He would later write that this was “to prevent intrusion,” but there must have been a few people present who wondered if they’d just been locked inside with a lunatic.

Sherman came back, took his seat and proceeded to launch into a highly detailed and downright hysterical tale of woe: how he scarcely got any supplies where he was stationed; how his forces were powerless for invasion and would only tempt a talented general like Albert Sidney Johnston to invade Louisville at any moment. How little training his troops had; how spies had infiltrated his army; how undisciplined volunteer companies were proving.

“You astonish me!” Cameron interjected, but Sherman didn’t think the Secretary of War should be astonished at all. And Cump was just getting started.

He lit a cigar. His eyes flashed. He complained that General Anderson had been promised 40,000 new Springfield rifles; he hadn’t yet received them. He complained that his men were still using old Belgian muskets and he couldn’t even unload these on the militia members who came to Louisville for arms. He complained that the men of Kentucky were themselves unreliable, saying, “No one who owned a slave or a mule could be trusted.”

Here, Cameron attempted to interrupt the tirade, turning to Adjutant General Thomas and asking if he knew of any unattached troops who might be diverted to Kentucky to reinforce Sherman, but Sherman was still ranting.

Deciding he needed a visual aid to complete his presentation, he walked over, took down a map of the United States and spread it out on a table for Cameron to see, telling the Secretary that he, McClellan, and Fremont each had a 300-mile front to protect: McClellan had 100,000 men, Fremont had 60,000, but a mere 18,000 had been assigned to him.

When Cameron asked him just how many men he required, Sherman stared at the Secretary a moment with his dark flashing eyes. The room grew quiet.

“For the purpose of defense,” said Sherman, “60,000, at once. For offense, 200,000.”

Cameron, still lying on the bed, threw his hands up in air.

“Great God!” he said, “where are they to come from?”

Sherman didn’t know and that wasn’t his concern. As a general, his job was to fight the enemy; Cameron’s was to insure he had enough troops to fight the enemy with.

We can picture Cameron finally sitting up at the end of the bed to face this unhinged general and perhaps Sherman sensed that the secretary might not be family or friend, either one. In truth, Cameron was a corrupt bureaucrat who’d soon be cashiered by Lincoln and replaced with the effective but irascible Edwin M. Stanton.

But that was months away, and at present the Secretary placated Sherman with promises he had no intention of keeping. Cameron might have been a crook and a liar, but he was a professional crook and liar. Sherman was so enchanted by the conversation that followed that he believed Cameron had been “aroused to a realization of the great war that was before” them. He felt at long last like someone had finally heard him.

The next morning, Cameron and his court headed for Cincinnati. They were hardly aboard the train before the secretary told his entire entourage that Sherman was “unbalanced and that it would not do to leave him in command.”

4. “William T. Sherman Insane”

Two weeks after this meeting, an article hit the pages of the New York Tribune. Ostensibly a report by Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas, documenting the Secretary of War’s visit to the Western Theater, the article focused on Sherman and had actually been written by Samuel Wilkerson, that quiet journalist in Simon Cameron’s entourage who’d sat quietly taking notes while Sherman unwittingly set his career on fire.

The report mocked the general’s request for 200,000 men as an absurdity and played up Sherman’s panic, all while painting Cameron as sage and compassionate. On reading Wilkerson’s article, Sherman was mortified—this was, in effect, a gossip column masquerading as a government document. He was also furious to discover that some of the men he’d been encouraged by Cameron to view as friends and family were members of the press—men who’d always been adversarial to Sherman.

Cump immediately wrote to Lorenzo Thomas, imploring the adjutant general not to underestimate the Rebel threat to Kentucky or ignore his own pleas for reinforcements. Then he floated the possibility of being removed from command.

The biggest casualty of Wilkerson’s hit piece was Sherman’s already-compromised mental state. He began to eat less, sleep less, somehow managed to smoke and seethe even more, pacing until four in the morning when the telegraph office closed and no more dispatches could be sent for the day, a cigar blazing between his teeth as he finally made his wheezing way to bed. Though his uniform was expensive and expertly tailored, he took on the disheveled air of a college professor, or a slovenly tycoon, adopting a stovepipe hat like the president—an accessory that suited Lincoln, but made Cump look like an outsized ventriloquist’s dummy.

Then, round the middle of November, Sherman found the bottom of the abyss he’d been sinking into since his arrival in Kentucky. His letters from these autumn days are filled with despair. Writing to his brother, the Ohio senator John Sherman, Cump revealed his delusional belief that the Rebels were somehow “planning a simultaneously attack on St. Louis, Louisville, and Cincinnati. They have the force necessary for success, and the men capable of designing and executing it.” Next came the most despondent words he’d ever commit to paper: “our Government is destroyed, and no human power can restore it.”

Over the decades since the Civil War, historians have theorized about the cause of the suicidal depression that closed its black hand around Sherman’s throat fall of ‘61: he was new to the vast pressures and responsibilities of a large command; his brilliance and great sensitivity made him uniquely vulnerable to hopelessness in times of war, particularly when things weren’t going well. Some point out that though Sherman’s superiors were grimly amused by his request for 200,000 troops, Cump ended up being right about the size of the army it would take to break the Confederacy’s back—actually, his estimates proved modest. While Sherman was indeed correct about troop numbers, this last thesis forwarded by biographers casts him as a Cassandra figure who saw the truth of what it would take to destroy the enemy, but unable to convince anyone else, was gradually undone.

While these various theories have merit, they fail to account for why the Sherman of 1861 was crushed under the burden he carried while the Sherman of 1864 took a much heavier weight on his shoulders and bore it so expertly. After he and his army of 100,000 troopers burned their way from Atlanta to the sea in the fall and early winter of ‘64, Sherman telegraphed Lincoln an ebullient message from Savannah, presenting the captured city to the president as a “Christmas gift.”

But there is an element of Sherman’s Kentucky sojourn that receives far too little attention. In October of ’61, Sherman had encouraged a guerilla force of Tennessee Unionists who were planning an operation to burn a number of bridges in the northeastern part of that state, hoping to thereby disable Confederate railroads in the region. Cump even committed his own troops to support these guerillas, then backed out at the eleventh hour, worried that by sending soldiers to assist with the mission he’d be leaving parts of southern Kentucky exposed to Rebel attack.

But the paramilitary members of this Tennessee operation did not back out. They were captured by Confederates, charged with treason, and hanged. When Sherman caught wind of this, he grew distraught. He was haunted by the execution of these brave men. As an irregular band of guerillas and not soldiers enlisted in the Union army, the Tennesseans were not under Sherman’s command, but he blamed himself for their loss, regardless, writing his brother a few days after their execution that “the men suffered death has been the chief source of my despondency. I may be chiefly responsible for it.”

Reflecting on his time in Kentucky in his Memoirs, Sherman would say that the execution of these Unionists “weighed on me so that I felt unequal to the burden” of command.

On November 15, Don Carlos Buell assumed command of the Department of the Cumberland. Relieved at long last of the position that had so tormented him, Sherman traveled down the river to St. Louis where he was placed on the staff of General Henry Halleck, commander of the Department of the Missouri.

But his torments were not yet over and his mental health continued to deteriorate. Everyone Cump worked with at his new post was either worried about—or alarmed by—him. A fellow officer by the name of Captain Frederick Prime became so concerned that he took it upon himself to write Sherman’s in-laws, the politically powerful Ewing family: “Send Mrs. Sherman,” he pleaded in his letter, “to relieve Sherman’s mind.”

Ellen arrived in St. Louis with their boys, Tommy and Willy, and found her husband in bad enough shape that she sat down to write a letter of her own—this one to her brother-in-law, John Sherman, informing the senator of Cump’s condition and begging him to help. Today, this would likely be called an intervention and intervene Senator Sherman did. He penned a sternly-worded missive to his brother the thrust of which was that Cump needed to pull himself together; he was under the influence of “some strange delusion” and had become “almost repulsive” in his interactions with others.

The departmental doctor in garrison at St. Louis agreed with John Sherman’s diagnosis and further added that, at present, Cump was incapable of commanding troops and hardly had command of himself. Sherman’s boss, Henry W. Halleck, began mentioning Cump to the newly-installed general-in-chief in his cables back to Washington, notifying George B. McClellan that Sherman’s “presence was having a detrimental effect on the troops,” that his “physical and mental system was completely shattered” and that he was “entirely unfit for duty.” If there has ever been a worse performance review of a U.S. Army general, I have not read it.

Sherman was granted a three-week leave and Ellen took him back to their family home in Ohio. There, matters grew even worse.

On December 11th an article appeared in the Cincinnati Commercial with the headline WILLIAM T. SHERMAN INSANE and under that bold declaration: “The painful intelligence reaches us in such form that we are not at liberty to disclose it that General William T. Sherman, late commander of the Department of the Cumberland, is insane. It appears that he was, at the time while commanding in Kentucky, stark mad.” There followed a series of wild and fraudulent claims: that Sherman had requested permission to pull out Union troops and retreat from Kentucky; that subordinates in Missouri had started disobeying the deranged general’s orders; that he had now been “relieved entirely of command.”

We know a great deal now about the psychological effects of public shaming, much more than people did in the 19th century. To be the target of this kind of depersoning—especially by the media—can cause an individual to completely crumble. A plethora of emotional problems can surface, and Sherman seemed to display every one of them. He was embarrassed, angry, isolated, felt his career had been destroyed and told his father-in-law that the Commercial’s allegations would “impair my personal influence for much time to come, if not always.” Most of all, he worried about the effects the article would have on the children who bore his name, confiding to his brother that, if not for his boys, he “should have committed suicide.”

Fortunately for Sherman, his wife was a tenacious woman who loved her husband fiercely. Under her care, he finally slept, ate, and took a break from the stress of military life. Christmastime found him continuing to entertain thoughts of drowning himself in the Mississippi, but Ellen managed to nurse him back to physical and psychological health. The enormous pressures of command, the guilt over losing men he felt ought to’ve been under his protection, and the public assaults on his character had caused his personality to collapse: now Ellen was building him back up, brick by brick.

Once he showed signs of improvement, she decided she’d heal the damage done to his career, launching a letter-writing campaign to rehabilitate his professional reputation and dispute the Commercial’s slanderous accusations. After sending several unanswered letters to Abraham Lincoln, she enlisted her father in the crusade and, on January 29th of the new year, the two of them traveled to D.C. to visit the president in person. Lincoln received them very cordially—Thomas Ewing was too influential a man to turn away—reassuring Ellen that he’d heard all about the newspaper’s allegations and didn’t believe a word of them. Lincoln had good reason to dismiss newspaper articles as idle gossip given he’d spent his time a decent amount of his time as an Illinois politician planting fabricated stories about his opponents in the Sangamo Journal.

Though the president didn’t make Ellen any promises, his words of support brought the Shermans real comfort—a therapy many received from Lincoln during his years in office. Ellen reported the president’s words to her husband and he felt bolstered by them as well. He was eager to return to service and prove himself worthy of his wife’s care and attention.

As for Ellen, she was confident her husband’s reputation would be wholly restored and that he would now “stand higher than ever.”

Sherman went back to St. Louis a changed man: calmer, quieter, more reserved than his fellow officers had previously seen him. In February, when Grant started winning battles on the rivers of northern Tennessee, it was Sherman—in Halleck’s estimation, “a born quartermaster” (that crucial officer in charge of sending soldiers and supplies to field commanders)—who made sure Grant got everything he needed to successfully press his attack. In Ulysses S. Grant, Sherman saw a determined man of action with a “simple faith in success,” as he’d later put it. Grant was a fighter—the only one the North seemed to possess at the moment—and a fellow Ohioan to boot.[xiv] Though Sherman outranked Grant, he began angling to get placed under Grant’s command. With Kentucky closed off to the Confederates after Grant’s twin victories at Forts Henry and Donelson, and Union armies seizing Nashville and sweeping through Tennessee, Sherman was again given infantry to conduct a reconnaissance-in-force and discovered that the Rebels were massing around Corinth, Mississippi, just across the border.

On the west bank of the Tennessee River, Sherman discovered a place named Pittsburgh Landing where steamboats might put in to unload troops, and just beyond the landing, a flat expanse that “strongly impressed” him as an “ample camping ground for a hundred thousand men;” it could, he reported, be “easily defended by a small command.” Grant and Sherman bivouacked here, though they were ordered by Henry Halleck not to attack the enemy that was assembling some miles away at Corinth, but rather to await Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio, presently en route from Nashville. Halleck said would shortly arrive himself to take personal command and lead their combined forces in a grand assault on the Confederates.

And so, early April of 1862, Sherman found himself with a division under his command once again—twelve infantry regiments, eight cavalry companies, three batteries of artillery—drilling his boys in the fields along the banks of the river, camping and waiting for Henry Halleck around a little church named Shiloh.

4. “My God, We’re Attacked!”

It was here, that Grant and Sherman were famously surprised by a large Confederate army on the 6th. Many have remarked that the Union army dropped its guard that Sunday morning. In truth, they’d hardly bothered to put one up.

The possibility of being attacked in this sylvan setting was never taken seriously by Sherman or Grant. The location seemed so peaceful with its flat fields and peach orchard, the sound of the Tennessee lapping the shore of the landing, the quaint Methodist chapel sitting there encouragingly, as if watching over the men. The generals’ main concern was being reinforced by Buell’s army—if it ever decided to show up. In the meantime, the troops played cards and wrote letters to their loved ones. Few gave credence to the idea of an ambush.

One of these few was an anxious Ohio colonel under the command of Sherman who believed he’d already seen Confederate troops marching on the Union camps. His commander thought he was just jumpy. On April 5th, the day before the battle, Colonel Jesse Appler spied gray-uniformed soldiers ghosting through the woods and sent another panicked message to Sherman.

Cump became enraged and he rode out to deal with the colonel himself. After his own wretched experience in Kentucky and those months spent sending frenzied telegrams to his superiors, Sherman wasn’t about to let an overwrought officer spread fear among his men. He’d quash any whispers about Tecumseh’s troops being excitable before they grew from murmurs to shouts. And while suffering ought to engender empathy and understanding, very often it breeds contempt. A man does not like to see his failings in another: this only reminds him of his own weakness.

Sherman let Appler have it, telling the colonel to take his regiment back to Ohio if he couldn’t master his fear, then continued to dress him down: “Beauregard [Confederate commander of the army across the Tennessee border] is not such a fool as to leave his base of operations to attack us in ours. There is no enemy nearer than Corinth.”[xv]

Sherman was badly mistaken in that second assertion, but partially correct in his first: P.G.T. Beauregard—the Confederate hero of the First Battle of Manassas—did not want to attack the Federals that Sunday morning. He held to the strong belief that his Rebels had already lost the element of surprise: he didn’t see how the Yankees could’ve failed to notice thousands of gray-backed troops moving through the woods just south of the Union camp.

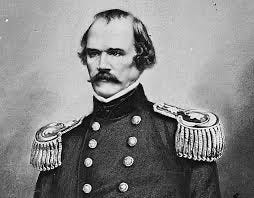

But he was overruled by the other Confederate chieftain at a council of war the night before. Albert Sidney Johnston, wanted to hit the Yankees as soon as possible. He told Beauregard that on Sunday morning, they would water their horses in the Tennessee or in hell. Saucy words, no doubt, but Johnston had reason to make grand pronouncements of this kind and then try to live up to them—Grant had thoroughly embarrassed him in seizing Fort Donelson just two months previous.

But to water his horse in the Tennessee River, Johnston and his men would have to sweep the field of Union soldiers. At dawn, just before the attack, Beauregard once again expressed his reservations and noted the enemy’s strength—the Confederates had about 40,000 men; the Union, 62,000.

“I would fight them if they were a million,” Johnston replied.

The sun rose at five-forty that morning. Around six a.m., as the Union men bivouacked south of Shiloh church saw to their breakfast, a great rustling came from the woods at the far end of camp. All at once, a number of deer bounded from the tree-line and went leaping among the rows of tents. Rabbits shot out from the underbrush; coveys of quail burst into the early morning light.

These were followed by a very different animal: Rebel troops clothed in gray or butternut, sprinting into the open with their rifles at port arms, unleashing that bloodcurdling scream that would set Yankee hearts pounding from southern Mississippi to Sharpsburg, Maryland. Some of the Union boys were shot down as they sat or stood. Others turned and started running toward the river. Many would not stop until the reach Pittsburgh Landing where they cowered under the bluff.

This assault so surprised the men of Sherman’s camps that even their commander was taken unawares. Cump had received no warning of this Rebel attack from Benjamin Prentiss—whose division was the first to be attacked that morning—and hadn’t heard the gunfire where he was bivouacked. A phenomenon known as acoustic shadowing was present in the topography just west of the Tennessee River that weekend. In this auditory anomaly, sound waves are disrupted by features of terrain such as trees, hills, or gullies, and even wind currents can factor into the equation, all resulting in a strange muting effect.

It wasn’t until Sherman spotted “glistening bayonets” in the distance that he mounted his horse and went trotting out to investigate. Riding beside him was his personal bodyguard, Private Thomas Holliday who went everywhere with the general. When a Minie ball erupted from the back of the private’s head and Holliday dropped from his saddle, the report of the rifle shot that had killed the poor man rolling out to reach him, Cump finally grasped the horror of what was happening. It must have been truly terrible for someone who’d been lectured time and again that he was overreacting, overestimating the enemy’s capabilities. He’d been so thoroughly gaslit by his superiors, he'd begun to gaslight the men serving under him. Did he recall the panicked warnings of Jesse Appler the day before, how savagely he’d spoken to this man who’d attempted to alert him to a very real threat? Perhaps, a grim vindication even flashed through Sherman’s mind and the past six months coalesced into four fateful words:

“My God,” he said, “we’re attacked!”

In one of the deserted Yankee camps, Rebels paused their attack to pillage tents and pilfer through the Union troops’ personal belongings, drinking coffee from the still-warm kettles, helping themselves to bacon sizzling in skillets. They even read the Federals’ mail in hopes of discovering what Northern girls were like.

When Albert Sidney Johnston rode up on his big bay horse, he was appalled to find Southern men behaving like common vandals and rebuked a young lieutenant emerging from one of the tents with his arms full of Yankee trinkets.

“None of that,” Johnston told the officer. “We are not here for plunder.”

Then Johnston thought better of his reprimand. It was probably best not to chasten a twenty-year-old who’d just overrun an enemy position at great personal risk and looked to be about to win the day. He leaned over in the saddle and picked up a tin cup from a table.

“Let this be my share of the spoils today,” he said.

He now wielded the cup like a cavalry saber, ordering his men into position, urging them on. Earlier that morning, riding along the front lines to deliver words of encouragement, he’d addressed an Arkansas regiment.

“Men of Arkansas,” he thundered, “they say you boast of your prowess with the Bowie knife. Today you wield a nobler weapon: the bayonet.”

On first glance, Johnston’s words seem like a standard battlefield speech. Most troops who fought at Shiloh that day had been ordered to fix bayonets. American generals in the early 1860s favored the bayonet charge as an indispensable tactic—particularly where soldiers came into close contact with the enemy.

But when we cast a colder eye on Johnston’s advice to those Arkansas men, we discover some rather troubling facts. William Rowley, Grant’s Military Secretary, would later report, “I do not believe in truth a single man was killed by a bayonet during the two days’ fight.”

The reason for this is both simple and sobering: soldiers at the Battle of Shiloh never came close enough to use their bayonets. The rifled musket they carried could kill effectively at 200 yards. Bladed weapons were now relics of past wars, but commanders were too seduced by the romance of these implements to give them up. They believed that to triumph in combat, you massed your men, threw volleys of lead at the enemy, then rushed up to deliver a coup de grace with the bayonet. Generals would order these doomed charges throughout the Civil War. Which meant four solid years of men sprinting up to fortified positions only to be shredded by enemy guns.

This is precisely what would happen during the Pickett’s famous charge on July 3rd at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, when Robert E. Lee ordered 10,000 men to take a one-mile stroll into intersecting fields of cannon and rifle fire. George Pickett, the general placed in charge of this suicidal maneuver, never forgave Lee for destroying his young soldiers.

“That old man had my division massacred,” Pickett bitterly remarked.

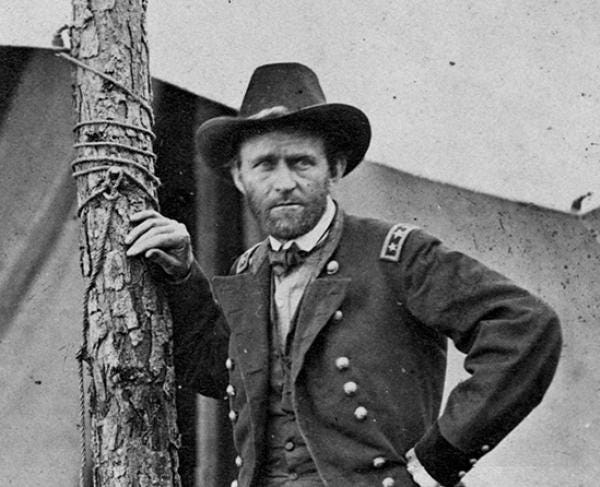

While Albert Sidney Johnston was riding along Confederate lines, dispensing advice and inspiration, General Grant was nine miles downriver at the Cherry mansion where he’d been quartering. He was eating breakfast when he heard the sound of artillery and realized something was horrible wrong. He boarded the steamboat Tigress and headed north.

He limped about the deck on crutches, eager to arrive on the battlefield. Two days earlier, the horse he was riding had slipped in a downpour and fallen on his leg. Grant’s foot became so swollen his boot had to be cut off, but luckily, he’d only sprained an ankle. When he disembarked in the Union rear at Pittsburg Landing around nine-thirty this Sabbath morning, his crutches were lashed to one side of his saddle like a pair of rifles.

There, at the landing, Grant took in a scene that would have sapped the fighting spirit of most combat commanders: “the entire slope from brow to basin was thronged with thousands of panic-stricken shirkers and stragglers.” The Rebels had managed to rout several brigades of Union troops.

Grant was shocked by what he saw, but showed no signs of distress. He had someone help him into the saddle, then rode out to speak with his corps commanders.

From the moment he mounted his horse, Grant was in mortal danger. Winston Groom calculates just how much, noting that a “rifleman […] was supposed to be able to load and fire three aimed shots a minute. Theoretically, then, if every rifleman in a brigade fired three times a minute, that would put 12,000 bullets in the air in that single minute, and from one brigade only. At Shiloh there were more than thirty brigades in the fight so one can only imagine the amount of deadly metal flying through the air in any given minute.”

Not counting cannon-fire, 360,000 bullets could have been cracking across the battlefield every sixty seconds, each one capable of puncturing flesh, shattering bone and pulverizing organs, cutting through veins and arteries like a shovel-blade through worms.

Grant paid no mind to such murderous math. He would locate one corps commander, speak to the man, then move on to the next.

He was conferring with his staff when a bullet slammed into the scabbard of his cavalry saber and sent it flying. The sword has never been recovered. Grant’s men were alarmed at how close they’d come to losing their general, but the unflappable Grant paid it no mind. He went to look for Sherman.

When he located Cump, he found the red-haired general just as prickly as ever. Sherman had been shot twice—once in the hand and again in the shoulder by a spent bullet which didn’t break the skin, but bruised it badly. The wound in Sherman’s hand, though hardly life-threatening, would’ve been extraordinarily painful—nerve endings concentrate in the hands and feet and make injuries to either excruciating.

Sherman had also had three horses shot out from under him and was now mounted on a fourth. Though he spoke even more quickly than usual, was a good deal more irritable, he’d managed to maintain his composure and effectively move troops under his command to plug holes in the Union line. He’d been surprised by the Rebels, but had also done his part to make sure Federal forces weren’t completely routed. And he was making Confederates pay for every inch of ground with blood.

What keeps a middle-aged man sitting five feet in the air with bullets cracking around his ears after a .58 caliber ball has slammed into his left hand and he’s had three horses shot out from under him? What cements a general in the saddle of that fourth mount, knowing at any moment another Minie ball could blow his bowels out his back or his brains into his lap? Other officers had retreated or at least gotten behind cover. No one would’ve blamed Sherman for doing likewise, putting a good-sized oak between himself and Rebel bullets or exploding shells.

But Cump didn’t do that. Instead, he sat on his perch in the air, exposed to Confederate marksmen and artillerists. Try to imagine the pain he was in. Have you ever closed a car door on your hand or missed the head of a nail and brought a hammer down on your finger? Multiply that sensation. The thought of such agony would be enough to send most men scurrying. Adrenaline will blunt the pain somewhat, but by the time Grant rode up to confer with Sherman, that would’ve burned off and every beat of his heart would have sent a stabbing pulse through his body.

And yet his response was not to run, but to wrap a handkerchief around the wound and shove his injured hand between his coat buttons, creating a sort of makeshift sling for his arm. Then he continued to ride back and forth among his men on the front line, shouting orders and words of encouragement. This was the same man who stayed up all night in Louisville six months before, dashing off panicked telegrams to Washington about Confederate armies that didn’t exist.

Or maybe it wasn’t the same man. The Sherman who sat his horse this April morning in the heat of the largest battle ever staged on the North American continent was a very different Sherman from the one who’d paced back and forth in the telegraph office in October of the previous year. He was rebuilding his reputation moment by murderous moment, crawling out of that pit of alleged insanity and incompetence; perhaps he even thought of those Tennessee Unionists he’d failed to support, hanged for their loyalty to the United States. Sherman would’ve known the kind of guilt that was waiting for him if he were to leave his boys on the field or abandon them to seek a field hospital at the rear—though, again, no one would have blamed him.

What kept Cump in that saddle in the face of likely annihilation or hideous disfigurement was who he was becoming. Every passing second was a farewell to the Sherman of Kentucky, the Sherman ridiculed by the newspapers of New York and Ohio. Another Sherman waited for him at nightfall—one whose name would become synonymous with indomitable courage and the destruction of America’s enemies; in another eighty years, the U.S. Army would name their most iconic tank after him. Moment by moment, Cump was fighting his way toward this legendary Sherman, and he was bound to reach him, if he could just stay alive.

5. “Johnston, Do You Know Me?”

By two in the afternoon, the Rebels had driven the Union line north toward Pittsburgh Landing and were flanking them, left and right. But Brigadier General Benjamin Prentiss and his Union men had retreated to a sunken road in the center of the battlefield that provided good cover for kneeling riflemen. When Grant visited Prentiss earlier, he’d told the intrepid brigadier to hold this position “at all hazards,” and hold it Prentiss did, though the pressure became hotter by the hour.

The Confederates began referring to Prentiss’s makeshift trench as the Hornet’s Nest, and Union hornets had repulsed wave after wave of Confederate assaults upon it. But now that the Rebels had Prentiss flanked, Confederate commanders decided to stage an all-out assault on the sunken road. The only problem was that a few Rebel brigades, seeing what had happened to their comrades who’d charged this entrenched position, absolutely refused to throw their lives away in another attack on it; the entire 45th Tennessee retreated and hid behind a fence. Tennessee Governor Isham Harris—who, when the Yankees took Nashville in February, joined Albert Sidney Johnston’s staff—managed to get these boys into formation for the big assault. They were to charge a peach orchard where Union Colonel Isaac Pugh and his men used both rifle and cannon to defend the southwestern approach to the angry Nest. A successful capture of the orchard and its guns would, in military parlance, turn the enemy’s flank and expose the sunken road where Prentiss’s men kept up a steady barrage of rifle fire.

But the terrified Rebels would not charge. General John C. Breckinridge—who’d been Vice President of the United States until the Lincoln administration took over—came riding up and reported on these uncooperative troops to Albert Sidney Johnston who had never heard of Tennessee boys backing down from a fight. Johnston turned to Breckinridge and said, “Then I will help you.” He went riding off to deliver yet another speech to the quaking Tennesseans.

“Men,” Johnston bellowed, once he’d reached the 45th and fixed his gray gaze on them, “they are stubborn; we must use the bayonet!”

Then he rode his big bay horse, Fire-Eater, down the line of Rebels, leaning from the saddle to touch the tin cup he still carried to the tips of their bayonets, a hollow clinking that Dopplered along the line. This act must have brought smiles to their young faces, even as it shamed them for their good sense. Johnston was showing his confidence in them. And what confidence it was, coming, as it did, from a genuine cavalier and model of Southern gallantry. Along with Jeb Stuart and John Singleton Mosby, Johnston was the closest thing to a knight the South ever produced.

He rode to their front and center, sat his horse, and reviewed them one last time, these troopers in their soiled butternut uniforms, lips blackened from biting off the ends of the paper cartridges they carried to charge their rifles, faces streaked with gunpowder and soot. The general would have smelled fear on them, that sharp scent of ammonia, the distilled essence men give off in combat, facing grotesque injury and excruciating death. Now that had gained their obedience, he might have been touched by their willingness to die for a cause they barely understood, if they understood it at all. None of these men owned slaves—rich man’s war, poor man’s fight was a whispered slogan of protest in the South—though they fought willingly, ferociously, on behalf of men who did. Men like Albert Sidney Johnston, who had owned a family of four in Texas—for what was a knight without his villeins? So, Johnston and his kind reasoned, though they could never square up to the fact that it was precisely this feudal spark in the American tinderbox that would burn their country to cinders.

The general turned Fire-Eater to face the enemy. He removed his hat and stood in the stirrups.

“I will lead you!” he roared, then spurred the big bay forward, the young Rebels rushing in behind him, screaming like devils.

Johnston and his boy soldiers went thundering toward the peach orchard. As Winston Groom has commented, it was the most “star-studded brigade charge in the history of the Civil War,” Governor Harris on the right, General Breckinridge on the left. Afternoon sunlight in the trees. A light breeze from the southeast. Thousands of pink petals fell in a steady shower. Seeing that the Tennesseans would complete the charge, Johnston and Harris veered their horses away and returned to the rear, but the Rebels kept advancing. Pugh and his Union men opened up on them artillery and their new Springfield rifles. These muskets fired a .58 caliber bullet of soft lead known as the Minie ball—named after its French inventor, Claude Minie. To the Confederate troops, the volleys of rifle-fire would have sounded like a great sheet of canvas being torn in half. The Tennesseans began to fall, toppling onto the carpet of pink petals, blood blossoming on their butternut uniforms, blood foaming on their lips, as Isaac Pugh directed storms of lead and iron-shot into their ranks.

Sometimes it’s difficult to tell why a particular unit falters and falls back and sometimes it’s very easy. Some positions are simply overwhelmed. Contemplating the chaos and confusion and the deafening roar of guns, it isn’t hard to see why a farm boy from Ohio, his rifle so fouled with gunpowder he couldn’t manage to ram another Minie ball down its barrel, watching through white clouds of musket-smoke as boys who, except for the color of their uniforms, looked much the same as him—easy to see why such a person might lay his weapon on the blanket of pink petals and begin to inch backward. Something about the line of howling Rebels overawed Pugh and his fellow Yankees. They wavered, then turned to run, abandoning their cannon and the peach grove to the Confederate charge.

Johnston had been sitting his horse, proudly monitoring this martial display. When Harris rode up to join him, he found the general looking “bright, joyous, and happy,” watching the young Rebels celebrate their victorious charge and the capture of Yankee cannon in the peach orchard. Sure, Fire-Eater had been shot several times, Johnston’s uniform was torn up by Yankee bullets, and one of his bootheels had been sliced in half.

“They didn’t trip me up that time,” he joked.

“Are you wounded?” Harris asked.

“No,” Johnston told him, then pointed out Federal artillery that had begun firing, asking the governor to deliver a message to Rebel gunners to “silence that battery.”

But after Harris had delivered the order and came riding back, he saw Johnston sway to one side and reached out to steady him.

“General,” asked Harris, “are you hurt?”

“Yes,” said Johnston, “and I fear seriously.”

Harris helped steer Fire-Eater into a nearby ravine and then managed to get the general off his horse and onto the ground.

Johnston’s face was ashen. He’d stopped answering Harris’s questions.

The governor began to ransack Johnston’s shredded uniform, searching for a wound, not finding one there, or there, or anywhere.

Then he happened to glance down and see one of the general’s boots had filled with blood.

Inspecting more carefully, he finally found what he’d been looking for, a bullet hole just behind Johnston’s right knee. The projectile had severed Johnston’s popliteal artery and the bright blood kept pulsing.

Harris started calling for Johnston’s surgeon, but the general had sent the man away to tend Union soldiers who’d been captured earlier that day.

The governor pulled out a flask filled with brandy and started pouring it into Johnston’s open mouth, thinking it might relieve the general’s pain, but the brandy just dribbled back out again.

Then the general’s chief of staff came rushing up, horrified to find his commander in this condition—on his back in the leaves, his face white as a winding sheet.

He knelt there beside the tall, handsome general and began to plead with him.

“Johnston,” he said, “do you know me? Johnston, do you know me?”

He asked the question over and over again, but the general never answered.

Johnston just lay there, staring up at nothing. His wide pupils reflected empty sky.

6. “Lick’em Tomorrow, Though”

By early evening, Beauregard called off the attack, deciding he’d inflicted enough punishment on the Union army for one day. He wired Jefferson Davis to tell the Confederate president he had Grant right where he wanted him and would finish him off in the morning.

A common saying among Rebels at the time held that one Southern soldier was “worth ten Yankee hirelings,” and Beauregard was fool enough to believe it. Never mind that while inflicting heavy Union casualties, he’d suffered 8,500 of his own or that he’d enter the fight on April 7th with half as many troops as he’d started with at dawn on April 6th. Never mind that Grant’s army was currently being reinforced by Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio and would launch a counterattack come morning with a combined force of 45,000 men—twice as many troops as Beauregard would be able to field.

Among combat commanders during the Civil War, Beauregard’s magical thinking about what he and his men could accomplish was matched only by George McClellan’s—who, on this April weekend, was still general-in-chief of the Union army, though Lincoln would replace him later that year. The president was plagued with the seemingly impossible task of finding a general who could stand up to the likes of Robert E. Lee. Eventually, Lincoln would recognize that the only man who could beat Lee was the one who, at dusk on this April day, was leaning on crutches beside Pittsburg Landing, watching as wounded boys were loaded onto hospital boats and steamed upriver in the gathering dark.

It started to raining. Thunder rolled along the bluffs of Pittsburgh Landing. Limping away from the river, Grant wrapped himself in a poncho and looked for a place to lie down. He crutched out across the field to an old, solitary oak, produced out of the darkness by camera flashes of lightning. He lay down and took shelter under the spell of its newly-sprouted leaves.

But his sprained ankle kept him awake and around midnight he hobbled back toward the river to a log cabin that had been repurposed by surgeons as a field hospital. Leaning there on his crutches, he quickly realized he’d get no sleep here either, not with the screams of men filling his ears, the ragged and pitiful pleas of young troops begging doctors not to saw off their limbs. He made his way back out to the field and lay down once more under the tree.

Which was where Tecumseh Sherman found him. Grant had shown real trust in Sherman that day and after all Cump had been though of late, it was greatly appreciated. A friendship was beginning to blossom between them, one of the most important partnerships of the war. Amidst the chaos and bloodshed, these two men had found each other. Grant realized that, like him, Sherman was a fighter, and Sherman realized Grant possessed the steely resolve needed to win this bloody affair.

They would become the Lennon and McCartney of Northern generals. Grant appreciated Sherman’s great intellect; Sherman appreciated Grant’s almost superhuman calm in the face of catastrophe. As Shelby Foote famously noted, Grant had “four o’clock in the morning courage”—the courage it takes to remain composed when a staff officer wakes you from a dead sleep to say the enemy has just turned your flank.

Sherman best described the reason they complimented each other (while giving ladling a good deal of praise on himself): “I’m a damn sight smarter than Grant. I know more about organization, supply and administration, and everything else than he does; but I’ll tell you where he beats me and beats all the world: he don’t care a damn for what the enemy does out of his sight. But it scares me like hell.”

On this rainy April night with lightning strobing the field, the two men under that lone tree were still getting to know each other, their friendship young as the leaves sheltering them from the cold, stinging rain.

“Well, Grant,” said Sherman, his wounded hand now wrapped in a proper bandage, “we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?”

“Yes,” Grant agreed, drawing a puff from his cigar, its tip reddening his cheeks like the coming dawn. “Lick’em tomorrow, though.”

7. “Whipped Like Hell”

Grant and Sherman weren’t the only sleepless soldiers at Shiloh that night. Behind Rebel lines, while other Confederates commanders congratulated themselves on their victorious day of fighting, Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest was growing increasingly restless. Something didn’t sit right with the cursing cavalryman. The most unlikely corps commander on either side of the war, Forrest had no military training and would rise from the rank of private to general in those four years—one of a handful of men to ever accomplish such a feat, and the only officer in blue or gray touched by some kind of native genius for warfare.

A barely-literate the son of Scotch-Irish settlers, Forrest had become a young millionaire by trading slaves in the Memphis market, and when war broke out, he raised a company of Southern rangers, funding the unit out of his own pocket. Strategy came naturally to Forrest—not the flawed strategy of West Point-educated generals who insisted their men charge up to entrenched positions only to be shot down, but effective, lightning-fast tactics that essentially used horsemen as mounted infantry. His men fought from the saddle with pistol and shotguns, revolutionizing cavalry tactics. Not even Sherman ever figured out how deal with Nathan Bedford Forrest, and was himself hounded by the so-called Wizard of the Saddle until the end of the war.

On this April night, after P.G.T. Beauregard called off the attack for the day, something kept gnawing at Forrest. If there was a Confederate general who could snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, it was the generally worthless Beauregard.

Wondering what was happening in the Union camps this evening, Forrest ordered several of his troopers to slip into overcoats taken off captured Yankees and conduct a scouting mission. When the men returned, Forrest learned that his fears weren’t the nighttime phantasms that assailed officers like George McClellan: his scouts informed him how they’d just seen steamship after steamship put in at Pittsburgh Landing, disembarking hundreds of fresh troops that would soon add up to thousands, tens of thousands—the reinforcements of Don Carlos Buell who Grant and Sherman had been eagerly awaiting.

Forrest didn’t care about being proven right; his entire concern was winning. He thanked his men for their reconnaissance, then went to look for a general to whom he could report this vital intelligence.

At six-four, he was a physically imposing man, rough around the edges and in the middle too. He had a bad temper, swore constantly, gambled huge sums of money at cards (he also won a great deal of time). He had a coarse sense of fairness that extended to all men who served under him, but not to men whose skin was darker than his own, and never to the enemy. He preached the black flag and practiced the lessons of these sermons: he didn’t take prisoners. If it had been up to him, all captive Union soldiers would’ve have been shot after interrogation.

Finding a general on this tempestuous night was no small feat. Moving from camp to camp in the driving rain, he encountered thousands of wounded, some in crude field hospitals—pavilion tents lit with lanterns—some just lying on the ground outside the tents, awaiting their torturous turns on the surgeons’ tables.

Picture Forrest walking in and out of the campfire light, this tall, marble-eyed man, lean as a wraith. He stalks in out of the rain, speaks to lieutenants, to captains, searching for men named William J. Hardee, or John C. Breckinridge, Braxton Bragg or James R. Chalmers, Pierre Gustav Toutant-Beauregard, walking among the anguished bodies of Southern boys, asking for generals, where are the generals. He has a message they must hear. Victory depends on it.

In the dark and driving rain, the ghastly wounds of young men glowed a strange shade of blue—surely an ill omen to the gray-clad Rebels. They called it Angel’s Glow for they had no germ theory, no idea that there were bacteria that thrived in this wet Southern wilderness, worked their way in wounds and gave off a blue luminescence. They must have believed they’d been visited by some devilry, an ignis fatuus to torment their minds with magic to match the agony wracking their broken bodies.

The colonel walks up out the night and glances them over.

“Where is General Chalmers?” he asks those tending the wounded, then stalks back into the rain.

Just after midnight, Forrest managed to locate Brigadier General James R. Chalmers and told the short Mississippian that the Yankees were presently being reinforced: if their own troops didn’t retreat or organize an assault to drive the Union men into the Tennessee River, come morning they’d be “whipped like hell.”

Passing the proverbial buck, Chalmers told Forrest to go finder an officer higher up the chain of command.

Forrest stomped off into the night and it took him another hour to find Chalmers’s superior, two of them in fact, both in the same tent: John C. Breckinridge and William Hardee.

But the generals were unimpressed by the intel Forrest handed them. Hardee sent Forrest back out in the rain to search for Beauregard who, after the death of Albert Sidney Johnston, was the highest-ranking Confederate on the battlefield.

But Hardee didn’t tell Forrest where to find the Creole general and he didn’t act on the intelligence Forrest had just delivered. If Hardee had or Breckinridge had ordered a night attack on the Unions whose ranks were swelling but still highly disorganized, the Rebels might actually have driven Federal troops into the river. They might have killed or captured Sherman. They might have made Grant a prisoner of war.

But no one took Forrest seriously that wet April night. The colonel marched through the cold downpour with his breath fogging the air, desperately searching for Beauregard’s headquarters until the sky went gray in the east and the sound of musket-fire rolled out to greet him with the sun.

At dawn on Monday, April 7th, Ulysses S. Grant took P.G.T. Beauregard to school, showing this aristocratic Southerner the proper way to launch and then press an assault. The outnumbered Confederates, exhausted from the previous day’s fighting, gave way before the Union counterattack which was bolstered with fresh men from Don Carlos Buell and Lew Wallace’s division. Here and there, Beauregard’s troops offered stiff resistance—Sherman, in his after-action report, claimed that his men encountered “the severest musketry fire I ever heard”—but just as Day One of Shiloh belonged to the Rebels, Day Two went to the Yankees. Riding over the field in the heat of battle, Grant lost a second scabbard to an enemy bullet. He’d been saved from injury or death twice in two days by this steel sheath, so it is a little surprising to recall that Grant wasn’t carrying a sword three years later when Robert E. Lee surrendered to him at Appomattox. If most Union officers had been rescued even once by such a martial accoutrement, they would have had one attached to their belts for the rest of their lives. It says much about Grant—seemingly untroubled by the thought of what enemy bullets might do to him, favoring plain private’s coats with his rank sewed on the shoulders—that he stopped wearing his sword altogether, leaving it back in his headquarters tent with the other finery issued to him. Accepting Lee’s surrender on April 9th of 1865, he kept apologizing to Lee for his muddy boots and that he’d forgotten to bring his saber.

Beauregard, who fancied himself a Southern aristocrat like Lee, even though he lacked Lee’s intellect, fighting spirit, and prodigious talent for strategy, realized he’d been beaten. He began withdrawing troops from the battlefield and by evening had ordered a full retreat back to Corinth. He’d taken a shocking number of casualties on this second day of fighting and many men would’ve been saved if Nathan Bedford Forrest had found his headquarters tent the previous night.

That’s assuming, of course, Beauregard would’ve listened.

8. “Kill the Goddamn Rebel!”