[31] “the war’s over”—the Mexican-American War (1846-48) which ended the year before this scene between the Sergeant and the Kid. This conflict between the US and Mexico concluded with a victorious America adding the entire Southwest to its growing “Empire of Liberty,” including the present-day states of Nevada, Utah, Arizona, California, and swaths of Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico.

[31] “plug hat”—any hat with a stiff crown and bill, such as a bowler or top hat.

[32] “blaze”—a white stripe down the center of a horse’s nose.

[32] “Lazarus”—a friend of Jesus. Jesus weeps when he receives news of Lazarus’s death, then travels to the man’s tomb and raises him from the dead (Gospel of John, Chapter 11). The sergeant is positioning Captain White as a Christ-figure—a metaphor McCarthy will have some perverse fun with in the coming pages.

[32] “halms”—stems or stalks.

[32] “town”—the town referenced here is San Antonio de Bexar (now just San Antonio).

[33] “deathbells”—a handbell rung to announce a death or funeral.

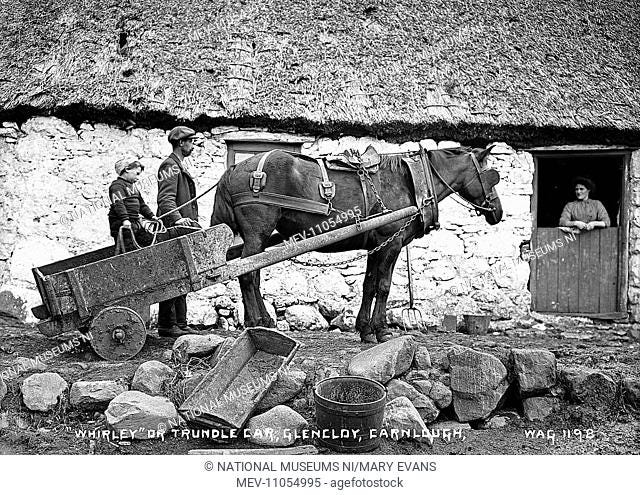

[33] “trundlecart”—a wheelbarrow that is pulled rather than pushed (the example above is being pulled by a horse).

[33] “sand”—parchment paper didn’t not absorb ink in the way its modern counterpart does. Captain White is using sand to dry the ink and prevent smearing.

[34] “ring”—when wax was used to seal letters, men of stature wore signet rings with an initial or crest in intaglio on their surface. They’d pool warm wax on a document, then knuckle their rings across the wax, leaving the raised impression behind.

[34] “settle”—a wooden bench with arms and a high back.

[35] “large revolver”—likely, a Colt Dragoon pistol.

[35] “nineteen”—the Kid is lying: he’s sixteen.

[35] “I was fell on by robbers…Mexicans and n*****s. They was a white or two with em. They had a bunch of cattle they’d stole. Only thing they left me with was a old piece of knife I had in my boot.”—more lies from the Kid. Here, he converts the kindness and generosity of the cattle drivers who fed him and gave him a knife in the previous chapter (p. 21-22) into racist opportunism.

[35] “What do you think of the treaty?”—Captain White is referring to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which ended the Mexican-American War, signed on February 2nd, 1848. As stated above, America achieved vast territorial gains in this Treaty. The Captain’s entire claim that the United States were somehow shortchanged is ludicrous.

[35] “Volunteers at Monterrey”—the Kid’s home state of Tennessee became the “Volunteer State” because of its contribution of citizen militia during the Mexican-American War. The Battle of Monterey (September 21-24, 1846) was a particularly nasty fight. Though US forces emerged victorious, the battle saw a great deal of close-quarters fighting—the Texas Rangers hacked holes in the walls of homes to pass from house to house without exposing themselves to gunfire in the streets. Famously, young lieutenant known as “Sam” Grant distinguished himself through feats of great bravery during those brutal September days. Twenty-two years later, he was elected the 18th President of the United States.

[36] “paid tribute a hundred years to tribes of naked savages”—a reference to the Comanche and the Apache who raided villages in northern Mexico. The raids of the Comanche were so costly for Mexico that the Mexican government invited Anglo-American colonists into Texas in 1824-25 in a ploy to place a meat barrier between their citizens and the Comanche—a plot that would lead to the Texas Revolution ten years later (1835) and then the loss of Texas to the United States ten years after that (1846). Ironically, this particular “tribe of savages” annihilates Captain White’s band of filibusters in the very next chapter.

[36] “Colonel Doniphan”—Alexander William Doniphan who, though badly outnumbered, won two battles against Mexican forces during the war.

[36] “manifestly incapable of governing themselves”—here, McCarthy has Captain White invoke Manifest Destiny—a belief popular among nineteenth century Americans that the US was destined to expand its empire across the continent. The term was first coined by journalist John L. O’Sullivan in a 1845-essay entitled “Annexation” where he argued for the annexation of Texas.

[36] “Paredes”—Mariano Paredes has been President of Mexico at the time of the Mexican-American War and helped get his country into a devastating conflict which Mexico was incapable of winning—against an industrial adversary looking for any excuse to seize Mexican territory in the American Southwest. Captain White’s geopolitical savvy is, at best, suspect.

[36] “Colonel Carrasco”—a Mexican Army officer who was frustrated by the Mexican government’s unwillingness to address Apache raids in Sonora.

[36-37] “Right now they are forming…obliged to travel”—one of the truly bizarre features of Captain White’s lecture is he speaks as if the US has lost the Mexican-American War. If he’d waited a year for the commission he speaks of, the boundary lines would’ve been drawn up, routes west secured, cut-throats dealt with. He could have prevented his head being pickled in a jar.

[37] “Monroe Doctrine”—President James Monroe articulated the position that no European power would maintain its foothold in North America: the continent would eventually belong to the United States.

[37] “mollycoddles”—people with excessive caution.

[38] “bobtails”—a dishonorably discharged soldier.

[40] “Lipan indians”—the Lipan People were a band of the Apache tribe, native to southwest Texas and northern Mexico. It’s interesting that we see them here in San Antonio, given Captain White’s remarks.

[40] “Karankawas”—the Karankawa People were a tribe native to costal Texas. It was widely believed by whites in the mid-nineteenth century that the Karankawas were cannibals, but there is no evidence to support this claim and it now seems to have been a lie used to justify driving them into complete extinction—which sadly occurred. By 1858, the Karankawa were all gone.

[41] “How many youths have come home cold and dead from just such nights and just such plans.”—once again, the narrator directly addresses the reader.

[41] “two and a half dollar gold piece”—a Liberty’s head quarter eagle.

[41] “Y sus botas”—“and his boots.”

[41] “Laredito”—a neighborhood that is now downtown San Antonio.

[42] “where by the light of a forgefire an old man beats out shapes of metal”—seemingly, a passing detail. When considered in the context of the most important passage in the novel (pp. 322-23), the phrase takes on fascinating shades of meaning.

[42] “Mennonite”—the Mennonites are a Protestant sect born out of the Reformation with very strict pacifist beliefs. While persecuted in Europe, the Mennonites enjoyed great freedom in America—a fact that explains this anti-war prophet’s boldness in addressing the Kid and his companions. This scene/character is a callback to Elijah from Moby-Dick, a man who accosts Ishmael and Queequeg, warning them against boarding The Pequod.

[42] “General Worth”—Major General William J. Worth, hero of the Mexican-American War. In 1849, Worth was still in Texas, bivouacked with his men along the Rio Grande.

Re Footnote 40 I recommend The Last Karankawas, by Kimberly Garza for a modern take on their legacy

I've started this novel a few times over the past few months, but I allowed myself to get distracted with other ones, so I'm starting from the beginning again, this time with your chapter annotations. One question -- a minor detail, but when Captain White asks the kid how old he is (Ch 3, pg34), is the kid lying when he says he's 19 (is he really 16 or so)?